Codex macOS: Orchestration-First Agent Desktop

What I Learned

After trying out Codex’s macOS app, here are the key things that stood out to me:

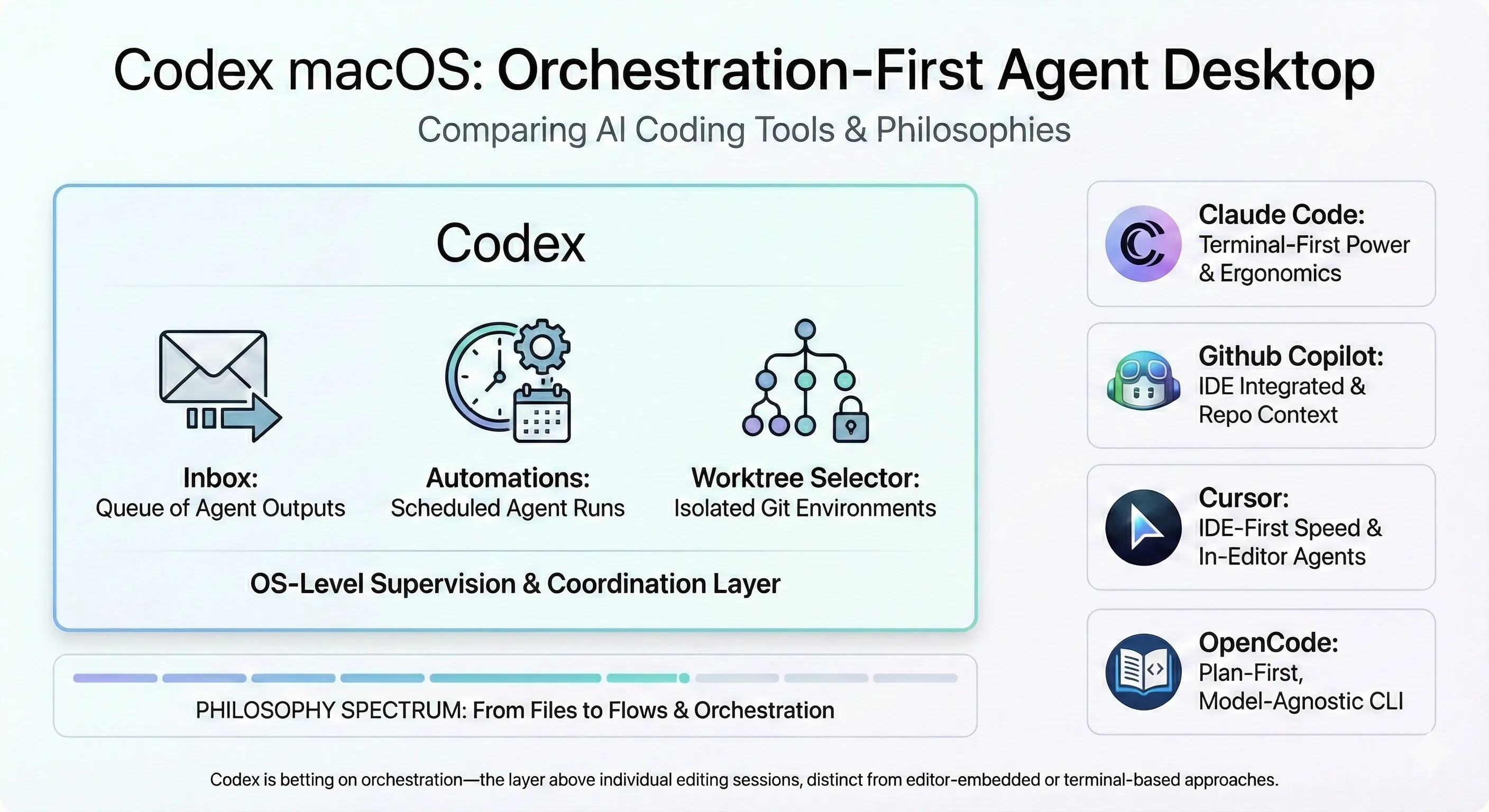

- It lives at the OS layer: Unlike the IDE plugins and terminal tools I’m used to, Codex operates outside your editor—supervising agents through an inbox, automations pane, and worktree selector.

- Scheduled automations are genuinely useful: I set up a few recurring agent runs that execute in isolated Git worktrees, and having results land in a reviewable inbox with desktop notifications actually changed how I thought about agent work.

- It’s positioning as a coordination layer: While Cursor optimizes for in-editor speed and Claude Code for terminal power, Codex is betting on orchestration—the layer above individual editing sessions.

The Philosophy: From Files to Flows

OpenAI launched Codex for macOS on February 2, 2026, and after using it, I think I understand what they’re going for. Rather than embedding AI deeper into your editor or terminal (the approach I’ve gotten comfortable with), Codex treats macOS itself as the control surface.

The first time I opened the app, three primitives jumped out at me:

- Inbox: A queue of agent outputs awaiting review. I realized I’d been constantly polling my terminal for agent completions but this eliminates that.

- Automations pane: Scheduled agent runs with configurable triggers. Think cron, but for AI tasks.

- Worktree selector: One-click creation and switching between isolated Git worktrees. Instead of

git worktree add.

After experimenting with it, the thesis became clear: as agents become capable of longer, more autonomous runs, the bottleneck shifts from writing code faster to supervising agents effectively. Codex (not unlike other coding agents) is betting that developers need a coordination layer that is somewhere to see what’s running, what finished, and what needs approval separate from the editor they use to write code.

It’s a different mental model than I’m used to. With Claude Code, I feel more in the loop constantly, prompting and iterating alongside my IDE. With Codex, I’m more of a supervisor checking completed work.

How It Works Under the Hood

Digging into how Codex is built helped me understand why it behaves the way it does. There are four main components:

Agent Supervisor This manages concurrent agent threads with rate limiting and resource allocation. Unlike IDE-embedded agents that typically run one task at a time, Codex can spawn multiple agents per request, each working in parallel on different aspects of a task. I tested this by having it refactor a component while simultaneously writing tests where both finished around the same time.

Worktree Engine Every automation or long-running task starts in a fresh Git worktree. This isolation means experimental agent runs never touch your main branch—you review the diff, then merge or discard. The one-click worktree creation from the UI was something I didn’t know I needed until I had it.

Sandbox + Permissions Three permission modes propagate to all agent operations:

- Read-only: Agents can analyze but not modify files

- Workspace: Agents can modify files within the project directory

- Full-access: Unrestricted file and network access

Tool calls outside the allowed scope fail immediately. This is critical for the unattended automations I set up. I could schedule a security scan with read-only permissions and trust it wouldn’t accidentally rm -rf anything. Coming from Claude Code where I manually approve every file change, this felt like a reasonable trade-off for background tasks.

Preview/Apply Layer Rich Markdown/MDX preview with explicit Apply actions that map to git/CLI steps. Every edit is auditable: you see the diff, approve it, and can revert at any point. This part felt familiar—similar to how I review changes in Claude Code before accepting them and to my markdown preview extension.

How the Components Fit Together

Automations: Where It Clicked for Me

The automation system is where Codex’s orchestration philosophy became concrete. I’ll admit I was skeptical at first—do I really need scheduled agent runs? But after setting up a few, I started to see the value.

Here’s how it works: you define a schedule (hourly, daily, weekly), pair it with a skill (a reusable prompt template), and Codex handles the rest:

- Creates a disposable worktree at trigger time

- Runs the agent with your specified permissions

- Pipes findings to the inbox

- Fires a desktop notification on completion

- Waits for your Apply/Revert decision

What I actually set up:

- Morning security scan: Weekly automation that reviews dependency updates and flags CVEs. Results are ready when I start my day.

- Test suite monitor: Hourly runs against staging, with notifications only on failures. This one caught a regression I would have missed.

- Documentation drift: Daily check that API docs match implementation. You could also potentialy use this to keep specs up to date.

Because runs are isolated in worktrees, I could delete failed experiments without git surgery. The ones that worked? Merged with a click. I liked how seamless this was.

What I Like About the Security Model

Codex’s sandbox isn’t just for interactive sessions—it propagates to background automations. This is the key difference from running agents manually: I could schedule unattended runs with confidence that they operate within declared permissions.

The model has three layers:

- Permission modes: Read-only/workspace/full-access set the ceiling for what agents can do.

- Tool-level enforcement: Individual tool calls (file writes, network requests, shell commands) are checked against the permission mode. Violations fail immediately with clear error messages.

- Apply/Revert checkpoint: Even with full permissions, file changes accumulate in a review state. You explicitly Apply to commit changes or Revert to discard them.

This creates a nice panic button for exploratory sessions. I let an agent run in full-access mode a few times, reviewed the accumulated changes, then Reverted when it went sideways—no git reset required. That safety net made me more willing to experiment.

How It Compares to What I’m Used To

The AI coding tool landscape has fragmented along architectural lines. Each tool optimizes for a different workflow, and I’ve developed strong opinions from using several of them:

Cursor 2.0 (IDE-first) Cursor redesigned its interface around agents in October 2025. Up to 8 agents run in parallel, each in its own worktree, but all within the editor. The Browser for Agent tool lets agents interact with web content. Best for: developers who live in their editor and want agents as first-class IDE citizens.

Claude Code 2.1.x (terminal-first)

This is my home base. Anthropic’s CLI tool for developers who prefer the shell. Skills hot-reload from ~/.claude/skills without restarting sessions. Extensive vim motions, Shift+Enter support across modern terminals, and /teleport to push sessions to claude.ai. Best for: power users who want agent capabilities without leaving the terminal.

GitHub Copilot Agent Mode (IDE + repo graph) Autonomous multi-file edits inside VS Code with a self-healing loop that monitors for compile/lint errors and auto-corrects. Tightly integrated with GitHub identity and repository context. The separate Coding Agent product runs in GitHub Actions for fully asynchronous PR generation. Best for: VS Code users in the GitHub ecosystem.

OpenCode / OpenAgents (plan-first, OSS)

CLI agents that distinguish between Plan mode (restricted tools, can only modify .opencode/plans/*.md) and Build mode (full access). Tab key switches between modes. Model-agnostic with 75+ LLM providers. Best for: teams wanting explicit approval gates and model flexibility.

Codex (orchestration-first) OS-level inbox, scheduled automations, and cross-repo supervision without coupling to a specific editor. The idea is that you might use Cursor for focused coding sessions, Claude Code for quick terminal tasks, and Codex as the coordination layer that schedules background runs and aggregates results.

The Philosophical Differences

The Trade-offs: Why I’m Not Switching

Here’s where I need to be honest. After using Codex, I’m not abandoning Claude Code or OpenCode. Here’s why:

I’ve invested heavily in Claude’s prompting style. Over months of use, I’ve learned how to prompt Claude models effectively for different tasks. I know when to use chain-of-thought, how to structure context for complex refactors, and what phrasing gets consistent results. Codex uses different models with different behaviors, and that built-up intuition doesn’t transfer directly.

My skills and commands are finely tuned. I’ve accumulated a library of custom skills in ~/.claude/skills that handle my common workflows—commit formatting, PR descriptions, code review patterns, specific refactoring approaches. These aren’t just prompts; they’re workflows I’ve refined through trial and error. Yes, I can ask Codex to read and import these skills but I’d need to invest time into making sure their instructions are understood and followed well within the environment.

The interactive loop matters for certain tasks. For exploratory coding where I’m iterating rapidly—trying approaches, asking follow-up questions, refining direction—Claude Code’s terminal-first design feels more responsive. Codex’s inbox model is great for “fire and forget” tasks, but for the back-and-forth of active development, I prefer staying in my terminal.

Model flexibility matters. This is where OpenCode shines and Codex falls short. OpenCode supports 75+ LLM providers, meaning I can switch between Claude, GPT-4, Gemini, or open-source models depending on the task, cost constraints, or availability. Codex locks you into OpenAI’s models. With Claude Code and OpenCode, I’ve developed preferences for which models work best for different tasks—Sonnet for quick changes, Opus for complex reasoning, sometimes a local model for sensitive code. That flexibility is something I’m not willing to give up.

Platform lock-in is a real concern. I develop on Windows part-time, and Codex is macOS-only. But this is where I see platform lock-in as a disadvantage for both Claude Code and Codex—Claude Code ties you to Anthropic’s models, and Codex ties you to both OpenAI’s models and macOS. OpenCode shines here: it’s cross-platform and model-agnostic, supporting 75+ providers. If platform and model flexibility are priorities, OpenCode is the clear winner among terminal-based tools.

Muscle memory and ergonomics. Vim motions, keyboard shortcuts, the way Claude Code handles multi-file context—I’ve internalized these patterns. Switching to a GUI-first approach means relearning basic interactions.

The caveat: orchestration at scale. That said, there’s one area where Codex genuinely appeals to me. For larger orchestration of automaton tasks—scheduling multiple agents across repos, managing long-running background jobs, and reviewing batched results—Codex’s inbox model is compelling. If I were running a fleet of agents doing nightly security scans, dependency updates, and documentation checks across a dozen projects, the OS-level coordination layer would add real value. I’ve also heard that GPT 5.2 (which powers Codex) performs particularly well on long-running tasks compared to other models—better at maintaining context and staying on track over extended autonomous sessions. That’s exactly the use case Codex’s automation system is built for. For now, my needs are smaller, but I could see reaching for Codex specifically for longer, unattended agent runs as those needs grow.

Codex isn’t trying to replace my primary coding tool. It’s positioning as a coordination layer. The question is whether I need that layer badly enough to add another tool to my workflow and whether I can live with its platform and model constraints.

Where This Could Go

Because Codex lives at the macOS layer, it has a natural path toward general computer-use automation that I find intriguing:

Cross-app workflows: Search the web, pull documentation, drop findings into the inbox, then open the specific worktree that needs the change. The OS layer means agents could coordinate across applications, not just within a single editor.

Context fusion: Combine browser results, local files, calendar events, and issue trackers into a unified plan before touching code. Today’s agents operate in silos; an OS-level orchestrator could bridge them.

Scheduled briefings: Morning automation that scans overnight logs, security alerts, and release notes across your projects, then opens targeted diffs or draft PRs. I’d start my day with a prioritized queue, not a blank slate.

Reviewable high-permission tasks: OS-level sandboxing and explicit Apply/Revert make browser automation and file operations auditable. The same patterns that make code changes safe could extend to broader computer-use tasks.

If You Want to Try It

Based on my experience, here’s how I’d suggest approaching Codex:

- Start with your existing workflow: Don’t try to replace your primary editor. Add Codex as a coordination layer and see if it fills a gap.

- Enable a low-risk automation first: Begin with something like a daily test run or weekly dependency check. Get a feel for the inbox flow before trusting it with more.

- Use worktrees liberally: The one-click creation makes experimentation cheap. Let agents try risky approaches in isolation.

- Graduate prompts to skills gradually: Once you have prompts that work reliably in Codex, save them as skills and schedule them. Don’t try to port everything at once.

- Keep your existing tools: I’m keeping Claude Code for interactive work and using Codex for background orchestration. They complement rather than compete.

My Take

Codex makes a specific bet: that the future of AI-assisted coding looks less like editing files faster and more like supervising agents with clear jobs, schedules, and guardrails.

If Cursor optimizes for coding velocity, Claude Code for terminal ergonomics, and Copilot for VS Code integration, Codex optimizes for coordination—the layer above individual editing sessions where you manage what your agents are doing across projects.

For me, the verdict is: useful addition, not a replacement. I’m keeping my Claude Code setup for the interactive, iterative work I do most of the day. But I’m also keeping Codex running for background automations—the security scans, test monitors, and documentation checks that I’d never remember to run manually.

Whether this approach makes sense for you depends on how you work. If you already have a terminal or IDE workflow you love, Codex probably isn’t asking you to abandon it. It’s asking whether you could use an assistant that runs while you’re not watching. For some workflows, the answer is yes. For others, the overhead of another tool isn’t worth it. I’m still figuring out which category most of my work falls into.

Stay in the loop

New posts delivered to your inbox. No spam, unsubscribe anytime.