Birdy: Responsible AI Audit of Twitter

Fictitious Case Study

Background

Birdy, a major social media platform, where users can post text up to a certain number of characters. It has also long faced criticism for its handling of hate speech. To address this, the platform launched CleanTalk, an AI-driven system designed to identify and remove hate speech content. Recognizing the importance of fairness and accuracy in content moderation, Birdy aimed to make CleanTalk a model of responsible AI deployment.

CleanTalk was designed to analyze posts in real-time, flagging content deemed as hate speech for review or automatic removal. The system’s effectiveness relied heavily on its training data - a vast collection of social media posts manually labeled by a diverse group of annotators from across the globe. Birdy believed that by leveraging a broad annotator base, CleanTalk could minimize bias and accurately reflect the varied understandings of what constitutes hate speech.

Deployment

The development of CleanTalk involved an extensive data collection and annotation phase. Birdy engaged with a wide range of annotators, including freelancers, NGO partners, and in-house teams, to label posts as hate speech or non-hate speech. The platform sought to ensure diversity among annotators in terms of demographic backgrounds, believing this would help capture a wide spectrum of perspectives on hate speech.

Upon deployment, CleanTalk was hailed as a pioneering effort in AI moderation, capable of discerning complex patterns of hate speech while accommodating the nuances of different cultures and languages. The system was trained on millions of posts, with the underlying assumption that a diverse annotator pool would mitigate biases.

Failure

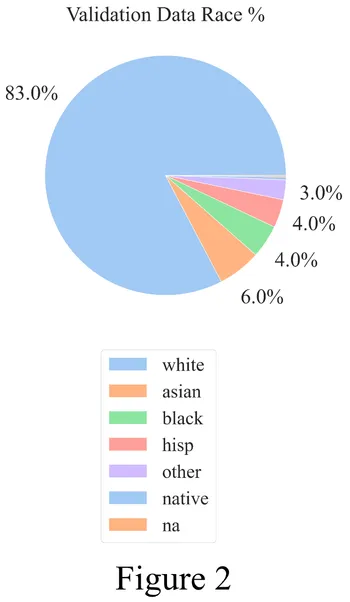

Despite Birdy’s efforts, CleanTalk soon encountered challenges. Users began to notice inconsistent moderation outcomes, where posts of a particular category were flagged and hate speech removed, while other offensive posts of a different category remained untouched. Some investigators began looking in the training data used by CleanTalk and found that it was disproportionately trained with white annotators and their ideas about hate speech.

Legal Action

The findings sparked a public outcry, leading to a high-profile class action lawsuit brought by plaintiffs (a group of users of Birdy) who felt they had been wrongly censored by Birdy. The plaintiffs alleged that Birdy, in using CleanTalk’s biased system, were unduly abridging their right to free speech. As part of discovery, the court appointed a third-party neutral auditing agency to further investigate CleanTalk and the initial allegations by users. The results of this audit, though perhaps not enough to hold Birdy liable or not liable, could help push the result of the class action in a particular direction.

Conclusion

The Birdy case study underscores the nuanced challenge of training AI models for complex tasks like hate speech detection. It illustrates that diversity in data annotation, while crucial, is not a panacea for bias. Ensuring fairness and accuracy in AI systems requires ongoing evaluation, transparency in methodology, and a commitment to understanding and mitigating the potential biases introduced at every stage of the AI development lifecycle. This case study also highlights the careful balancing act that systems like CleanTalk must endeavor to navigate: how do we decide what is considered hate speech and how do we prioritize user safety while also ensuring free speech?

Audit Context

Objectives

Birdy must ensure fairness and accuracy in its content moderation to ensure that all users feel safe using the platform. Given the case study where it was noted that offensive posts of one category were flagged when posts of another category were not flagged, it is critical that Birdy considers legal and technical recommendations to reduce bias in its system amongst different kinds of users. Birdy also needs to find a way to balance interests with its role as a social media platform where content should be moderated versus freedom of expression.

Prospective Auditors

Our prospective auditor would be a court-appointed neutral auditor. This makes the most sense in a class action context given that this is a role already used in such cases.

What/When of Audit

We are auditing Birdy’s content moderation model, which takes in a post and outputs whether or not it is offensive. We seek to understand how the demographic background of data annotators influences Birdy’s hate speech detection model. We aim to identify any bias in the data and in model development, with certain choices that were made.

The audit is conducted during the discovery phase of the class action lawsuit.

Methods, Tools, Metrics, and Standards

-

Legal

a. Debates about content moderation consistently center on the question of who gets to decide what warrants being taken down. There may be certain areas of general consensus (for example, CSAM), but it becomes much less clear in the realm of hate/offensive speech.

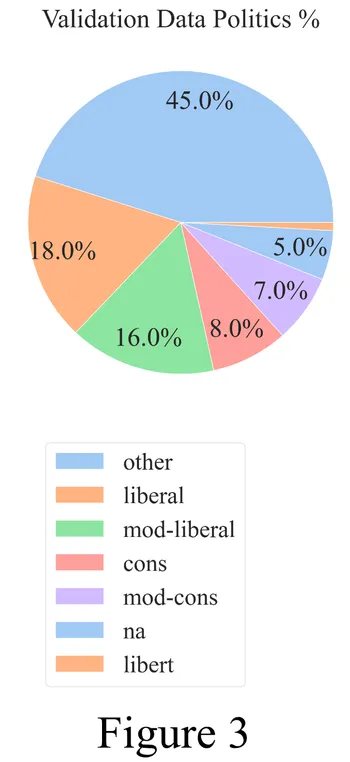

b. In order to measure fairness, we’ll be specifically looking at the standard deviation of TPR based on the annotator’s demographics. A high standard deviation would therefore suggest that there is wide variety in the TPR between the different groups of annotators. This, compounded with the fact that 80% of the dataset is made up of white annotators, would give us reason to pause and consider the implications of enforcing a system that is so heavily skewed toward one perspective.

-

Technical: Data collection

a. Social bias frames dataset has text paired with Y/N offensiveness annotations (no, neutral, yes) along with the demographic information about annotators originally collected from various online communities from a University of Washington study

b. Neutral labels were preserved to avoid flagging a non-offensive tweet → however it leads the model to be more uncertain so we considered neutral as an incorrect classification

- Neutral labels act as a way to “regularize” the models predictions, allowing us to control unfamiliar examples

- Consequently neutral predictions can directly be analyzed by human annotators to revise the model performance

-

Data preprocessing

a. Data entries with missing labels were dropped from the dataset

b. Train and validation sets provided were merged and then split into demographic subsets

c. Each demographic subset was then split into an 80-20 percent train-validation split

d. Test set was kept as is and treated as untouched holdout set for further performance analysis

-

For each demographic subset:

a. Fine-tuned pretrained Distil-Bert model to predict if text is offensive for 450 training steps, measuring train and validation performance

-

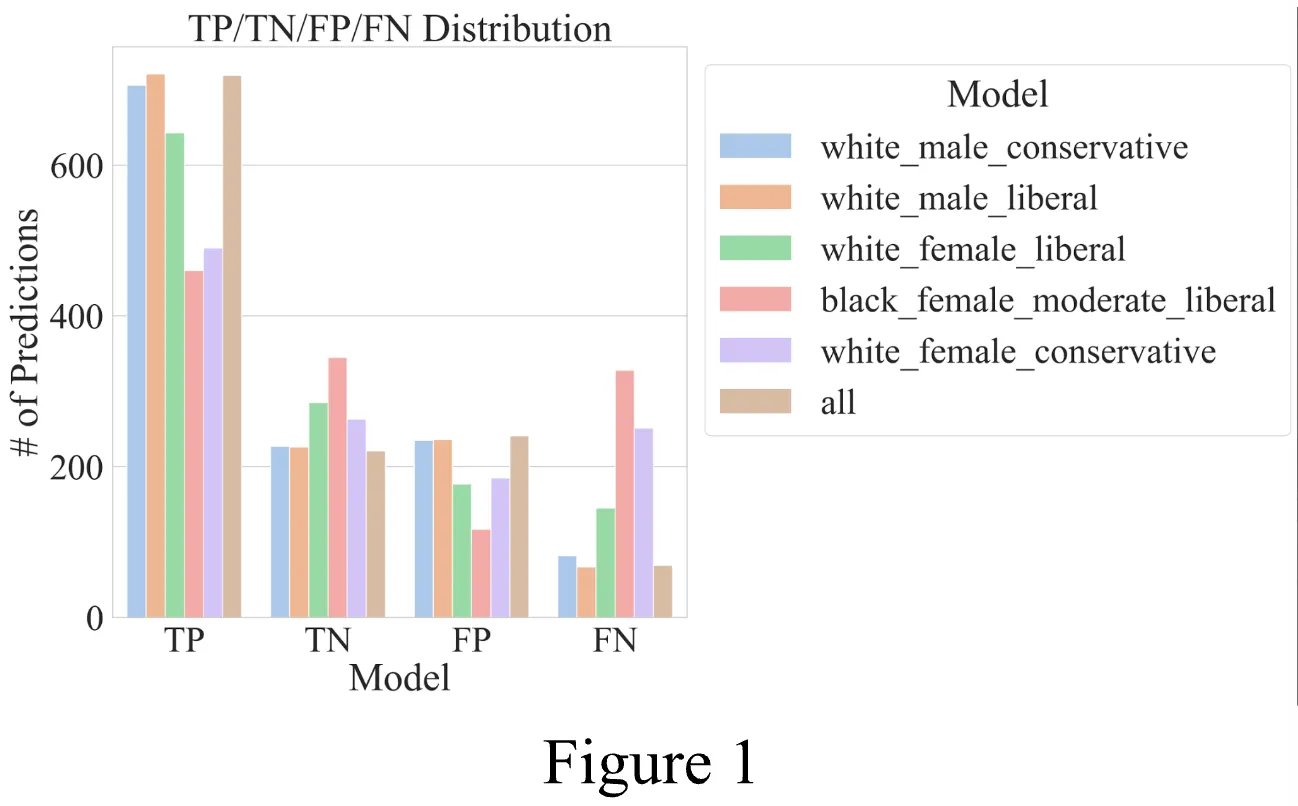

Measure discrepancy between each model in training, validation, and holdout set via metrics of FP, TP, FN, TN, precision, recall, ROC-curve analysis.

Case Study Analysis

Stakeholders

- Social Media Companies: want to more consistently moderate their hate speech using this system, flaws in the system could backfire on the social media companies & create new problem

- Individual Users: tension & differing interests between users who (a) posted harmful content and (b) were exposed to harmful content and feel like they’ve been harmed

- Civil Rights/Advocacy Groups: Many groups, like the ACLU, have advocated for social media companies to implement more specific hate speech policies. However, they’ve also pointed out that social media companies tend to remove posts by certain demographics over others – even if the content is the same.

- State Legislators: Several states, such as Texas, have proposed legislation that prohibit social media companies from discriminating in their content moderation on the basis of viewpoint. They would likely prefer a more hands-off approach to content moderation where most things, unless truly dangerous or advocating for violence, are permitted.

- EU: While this algorithm is based in the United States and will be subject to its laws, the EU might have an interest in encouraging Birdy to take more stringent measures to protect its online users.

- Brands/Advertisers: Advertisers want to appeal to a broad audience and may not (for the sake of their brand) want to place ads on a platform they feel is hosting hate speech. One example of this is X. After Elon Musk endorsed an anti-semitic conspiracy theory on X, several major brands paused their activity on X.

Human Values

-

Freedom of Expression/Freedom of Speech

-

In the United States (particularly when compared to other jurisdictions like the EU), we have a uniquely strong tradition of free speech. As seen in past court decisions (such as Snyder v. Phelps), we tend lean toward allowing speech even if it is blatantly offensive or harmful to certain groups. While the freedom of speech of users vis-a-vis the social media company isn’t a legal standard since these companies are private entities, it’s still a significant human value to consider.

- It is also incredibly difficult to create one general definition of hate speech. Each person will have their own unique interpretation of the term. Hence, freedom of expression also cautions us from over-moderating content and forcing one group’s idea of hate speech onto others.

-

Content moderation decisions have also been interpreted as the social media’s editorial discretion. One current example of this is a recent decision by the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals in NetChoice, LLC, et al. v. Attorney General that struck down portions of a Florida law requiring social media platforms to moderate content neutrally. Hence, while bias may be found via this audit, the question still remains unclear regarding what can be done from a legal standpoint.

-

-

Fairness

- Content moderation systems inevitably have to decide what their definition of hate speech is. We care about fairness in content moderation regarding (a) the way that the rules are consistently/inconsistently applied and (b) who gets to decide what is hate speech. This audit will focus primarily on (b).

-

Transparency

- This human value takes a bit of a backseat in the context of this audit, but it is nonetheless still important. Birdy’s users have a right to know how they are being moderated and Birdy has a responsibility to make this information accessible somewhere on its platform. This responsibility also extends to making users aware of CleanTalk and how CleanTalk works. While Birdy may have its rules of conduct explicitly written out, ensuring transparency also means explaining how CleanTalk enforces these rules and how it was trained to do so. This audit seeks to expose this and help make it known to the plaintiffs in the class action.

Life Cycle of the System

The Machine Learning Life Cycle of CleanTalk involves the following procedures:

The system is deployed on Birdy’s social media platform via an API developed by CleanTalk that parses the text of users tweets using a machine learning model and returns the sentiment of the text.

The system is both monitored and controlled by parties by Birdy and CleanTalk. For purposes of transparency, Birdy makes information about their use of CleanTalk known in their terms and conditions as well as in their rules and policies. A team at Birdy occasionally monitors and reviews the posts that are flagged as toxic. Birdy ultimately has the final say on the system’s actual application to its users. CleanTalk developed the algorithm through a process of data collection and annotation. CleanTalk will oversee the actual training (and subsequent retraining) of its system. It has broader control over what text will be flagged as toxic and the sensitivity of its algorithm.

The system will be periodically retrained every six months by CleanTalk offline to stay up to date with new terminology, trends, or slang. This retraining process involves the following like a typical ML DevOps pipeline:

A preprocessing algorithm will be applied to tweets that happened during the new period on Birdy’s platform. Additionally, to introduce diversity in data, a small portion of text will be scraped from openly accessible social media platforms. A sample of this processed data that is deemed to have a reasonable quality via a downstream algorithm will be assigned to annotators to identify the sentiment of the text.

Multiple diverse annorators will label the same text for sentiment and this will be added to a retraining dataset. The diversity of both the annotators and the dataset is crucial to ensuring fairness. The existing model will be fine-tuned using state-of-the-art techniques in natural language understanding and standard evaluation metrics such as precision, recall, accuracy, etc. Part of the model’s training will involve supervised learning with the annotator’s data and ground truth label of the majority annotation.

The new ML model’s performance will be compared to the old model. After ensuring the new model’s performance is better than the old model according to previously stated evaluation metrics, the system will be accessible as an API endpoint to Birdy’s engineering team.

Audit Question / Issue

Question

Is Birdy’s use of CleanTalk resulting in unfair and biased content moderation that unfairly abridged certain users’ freedom of expression?

Why This Matters

This question is important from a desire to protect the user’s freedom of expression while still maintaining a fair and safe online environment. Any content moderation system will inevitably run into the issue of users feeling like they were unfairly censored; there will never be one single definition of what constitutes hate speech, nor what the necessary response to hate speech should be. Thus, while we shouldn’t expect a perfect system, we should expect it to have the cultural nuance to balance the two aforementioned interests as best as possible. If we find wide discrepancies based on the annotator’s demographics, we have reason to be concerned.

Expected Findings

From a preliminary assessment of the data used to train the system, we can already see a significant bias. 80% of the annotators are white. While this is probably reflective of other biases in the tech workforce rather than any intentional design choice, we expect that the audit will expose issues associated with this. These discrepancies, notably discrepancies in the TPR rates between different groups of annotators, will point to an unfairness in the content moderation system that we should be concerned about.

Methods

Normative Question

Is Birdy’s use of CleanTalk resulting in unfair and biased content moderation that unduly abridges certain group’s freedom of expression? (Also: Who gets to define hate speech? Is a super robust/strict content moderation system desirable?)

- We need to contextualize this audit in a value-based framework centered on free speech, user safety and content moderation.

- Content moderation decisions by social media companies are interpreted, to some degree, by courts as them exercising their editorial discretion under the First Amendment. So, even if the audit does find bias or issues with their data collection, it’s not immediately obvious what can be done to rectify this or if anything should be done. (example: Florida law regulating content moderation on the basis of viewpoint was recently partly struck down by the Court of Appeals.)

- Bias is undesirable and we want a consistent content moderation system. However, we also have to balance this interest with the US’s strong free speech tradition. Thus, while high TPR’s demonstrate the accuracy of the system, users still may not agree that what is considered “toxic” is in fact toxic. While this issue may never be fully avoided (people will always disagree with what is considered toxic), at the very least the impact can be lessened by consistent TPR across different groups of annotators.

Technical Methods

- Identify how model performance varies based on the annotator demographic that it is trained on → does this vary among demographics?

- False positive rate vs true positive rate (ROC curve) to visualize model performance and choose threshold for considering a model biased

- Analyze false positives (model is too strict on certain posts) and false negatives (model is not strict enough in enforcing moderation) and if it varies among demographics on the same test set

- Based on above analysis, determine threshold for classifying model as unfair

Findings & Conclusions

Model Bias and Dataset Composition Analysis

Definitions

Model Bias ()

For our evaluation, we define model bias () as the standard deviation of the true positive rate (TPR) of the model concerning a certain demographic. For example, the model shown in Table 1 was trained on a random subset of data and validated against separate test sets, with a .

| Label | white_male_conservative | white_male_liberal | white_female_liberal | black_female_moderate_liberal | white_female_conservative | all |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPR | 0.896 | 0.915 | 0.816 | 0.584 | 0.661 | 0.912 |

| FNR | 0.104 | 0.085 | 0.184 | 0.416 | 0.339 | 0.087 |

| TNR | 0.491 | 0.489 | 0.617 | 0.747 | 0.587 | 0.478 |

| FPR | 0.509 | 0.511 | 0.383 | 0.253 | 0.413 | 0.522 |

Table 1

Fairness Metrics

Fairness is a comparative metric of bias, where:

- Models with lower are considered more fair

- Models with higher are considered less fair

Note: Models are not considered ‘fair’ in absolute terms, rather, they are comparatively ‘more fair’ or ‘less fair’ than other models.

Dataset Composition ()

We define composition () as the percent makeup of a dataset regarding a certain demographic. For our dataset, the racial composition is:The dataset bias () is calculated as the standard deviation of , giving us .

Training Data Analysis

For our white male conservative demographic:

This results in .

Performance Evaluation

The model performance shows:

Key Findings

-

Model Performance: Models trained on white male data demonstrate superior performance compared to those trained on white female or black female data.

-

Dataset Bias Impact: The high value in our dataset explains the poor performance of models trained on minority racial groups, as the dataset is skewed towards white people.

Content Moderation Implications

Observed Biases

- White male annotators show higher TPR rates

- 80% of annotator dataset comprised of white males

- Significant TPR disparities between demographics

Challenges

- One-size-fits-all moderation standards prove problematic

- Risk of:

- Inaccurate content flagging

- Potential freedom of speech impediments

- System inconsistency

Impact on User Engagement

- Both strict and lenient moderation can create chilling effects

- Marginalized groups face disproportionate online hostility

- Risk of reduced participation in digital discourse

Recommendations

Section 230 (Policy Recommendations)

Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996 is a fundamental law that shaped the Internet. It is a legal provision that protects Internet service providers from being sued for content published by third parties on their sites. It states: “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be considered the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider”. This provision was introduced to encourage online companies to moderate their content without fear of being held responsible for anything posted by users. Article 230 also allows social platforms to moderate their content by deleting messages that do not comply with the platform’s ethical standards, provided they act in “good faith”. Clearly defining what constitutes ‘good faith’ in the context of Section 230 is crucial. The notion of good faith is often open to interpretation and can be exploited in different ways. For example, a company that deliberately moderates a population category may be considered discriminatory. In another case, if an individual A is moderated for similar content for which an individual B is not, if the case is isolated, this could be attributed to an error or lack of attention. We could therefore assume that the company has not acted in “bad faith”. However, if suspicious moderation is observed within the same platform, and the latter invokes vague arguments such as a lack of technical, financial or human resources allocated to moderation services, it would be essential to establish a clear audit process to remove any ambiguity about the notion of good faith. This could include financial audits to verify the real existence of a lack of resources, and ethical or internal audits to assess whether moderation is truly intentional. Defining this term more precisely would help Birdy comprehend the legal requirements around moderating content on its platform. Having an explicit understanding of what qualifies as acting in ‘good faith’ would allow Birdy to reduce the risk of lawsuits by verifying that its moderation practices conform to legal criteria.

Exploring Further Cultural Nuance (Birdy-specific recommendation)

The conclusion of this audit still has several gaps. For instance, we focus specifically on English text and say nothing about other languages. Second, the demographics are limited to race, gender, and political orientation but there is nothing about nationality. However, defining objectionable content is highly nuanced and can vary significantly across countries/cultures, even among English-speaking individuals. What may be considered an inoffensive joke in South Africa could be viewed as harassment in the United States. It is therefore recommended that Birdy conduct a comprehensive audit to align and assess how their use of CleanTalk seeks to balance these varying cultural nuances. Specifically, the audit should articulate granular guidelines for discerning when constructive criticism crosses into a personal attack, when humor becomes a form of harassment or hate speech, and when repeated offensive behavior constitutes a violation of community standards. These threshold definitions should draw from established legal precedents as well as consultations with subject matter experts - including legal scholars, psychologists, and human rights specialists - to ensure the guidelines are fair, contextually appropriate, and consistent with ethical principles for the online environment. With well-defined policies aligned through a rigorous auditing process, platforms like Birdy can more effectively safeguard their user communities while upholding open and respectful dialogue.

Human-in-the-Loop / Procedural Justice

In tandem with a more balanced and diversified content moderation process, Birdy should implement a stronger human-in-the-loop, beyond just having someone occasionally review the posts that CleanTalk flags as toxic. Along with providing users the reasoning behind their content removal/flagging and the policies that have been violated, users should have access to clear-cut tools to be able to appeal the decision should they disagree with the decision. Many social media platforms, such as Instagram and more recently Snapchat, have integrated this function as a way to correct any possible shortcomings of the content moderation system. Moreover, the appeals process upholds the fundamental principle of free speech by allowing individuals to challenge censorship and have their voices heard in the digital public sphere. Doing so might also mitigate recidivism as offering an appeals process ensures procedural justice. Furthermore, integrating a stronger human-in-the-loop aspect not only enhances transparency and accountability but also ensures a more nuanced understanding of context, cultural sensitivities, and intent behind user-generated content. By offering users the opportunity to appeal decisions, platforms foster trust and empower users to participate in refining community standards, ultimately leading to a more inclusive and balanced online environment.

Technical

Model Monitoring

- Continuously monitor performance of model in production

- Introduce logging for number of posts blocked for demographic groups

- Measure user satisfaction of system via surveys

- Measure number of likes and dislikes for system

- Recommend using multi-modal LMs to filter out text, image, and audio

- Diversify training data

- Original training data was heavily imbalanced, with 80% of the annotators being white

- Any imbalance in training data directly affects performance of model → it is critical for Birdy to take proactive steps to ensure training data for content moderation is balanced among different annotator demographics

System Design

- When user clicks on a Birdy post, they can either label it as offensive or do nothing and Birdy can use this to further train the model → reinforcement learning human feedback a. Periodically, ask user if this filter was effective.

- Demographic-based filtering, enabled by user through profile page

- Simple keyword filtering (non-machine learning approach for more fine-grained control of filtering by users) where users can specify certain content they do not want to see

Summary

The audit of CleanTalk reveals biased training data leads to biased models and moderation outcomes, while also highlighting the concerns about content moderation and freedom of speech. Exacerbated by an unbalanced dataset of predominantly white annotators, models trained on biased datasets perform worse in fairness metrics. The audit revealed that models trained on white male data perform much better than those trained on white female or black female data, highlighting a detrimental instance of data imbalance. Imbalance present in the training data and testing data reveals that a one-size-fits-all approach to content moderation poses a serious risk of flawed and inconsistent results. In light of this audit, we encourage CleanTalk to further diversify its training to data and implement a human-in-the-loop for appeals. Policymakers may also consider Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act and what exactly “good faith” content moderation looks like.

👥 Collaborators

- Amudha Sairam (UC Berkeley)

- Arthur Clenet (UC Berkeley)

- Rena Lu (UC Berkeley)

- Safa Basravi (UC Berkeley)

- Sam Wu (Boston University)