Cartoonify: Cartoon Style Transfer + Generation

Introduction

The main objective was to apply style transfer in the context of diffusion models to generate more convincing “Disney”-style images from source images of people. To achieve this, we needed a deep understanding of the diffusion model’s architecture. The particular diffusion model employed in our project integrates a Variational Autoencoder (VAE), a U-Net architecture, and the CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pretraining) model.

Methodology

We used the latent diffusion model: stable-diffusion-v1.5. First, we collected the images of modern Disney characters, animals/objects, and landscapes. We followed DreamBooth, a training technique that updates the entire stable diffusion model with a few curated images. Since we chose to train the model with DreamBooth technique, we did not need a large dataset. In total, we collected around 200 images from Youtube, Google, and Pinterest. They were resized to 512 x 512. For higher quality, the background of images had to be white or black.

After collecting the data, we tried to train the model and text encoder with prior preservation. Prior preservation uses additional images of the same class we are trying to train as part of the fine-tuning process (regularization). Before training the model, we set approximately 40 parameters in advance. The specifics of the training parameters are as follows:

- Pre-trained Model: We utilized the ‘stable-diffusion-v1-5’ model from RunwayML as our starting point, with the ‘main’ revision indicating the use of the latest model variant.

- Variation and Precision: The model variant ‘fp16’ was selected for training, which uses 16-bit floating-point precision. This choice was instrumental in optimizing the training speed and memory usage without significantly compromising the model’s performance.

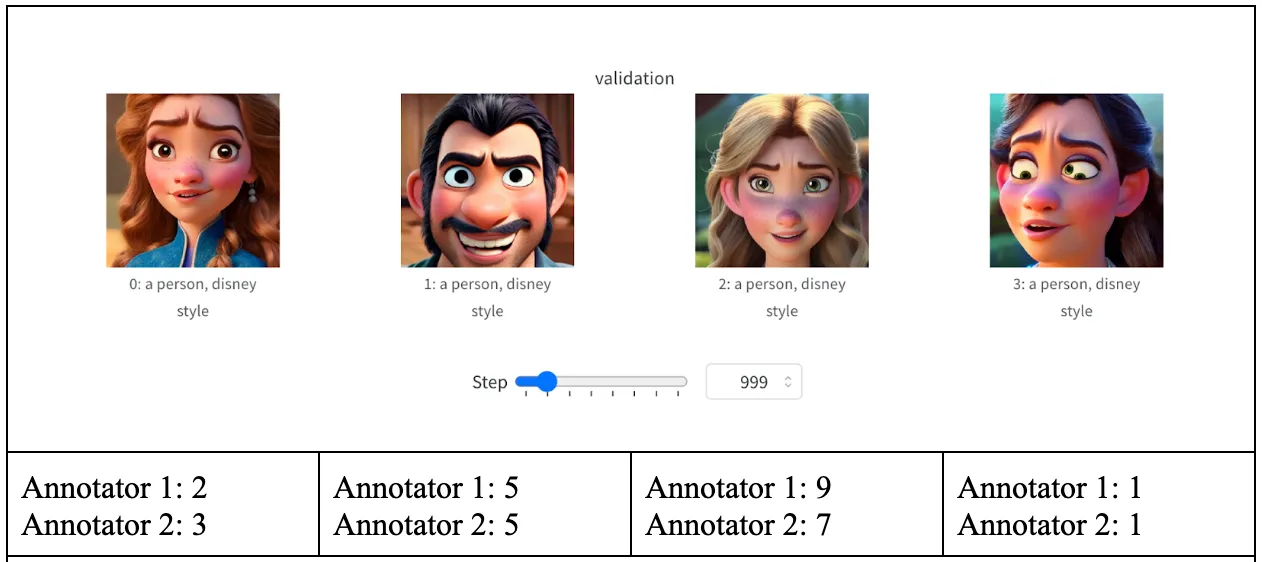

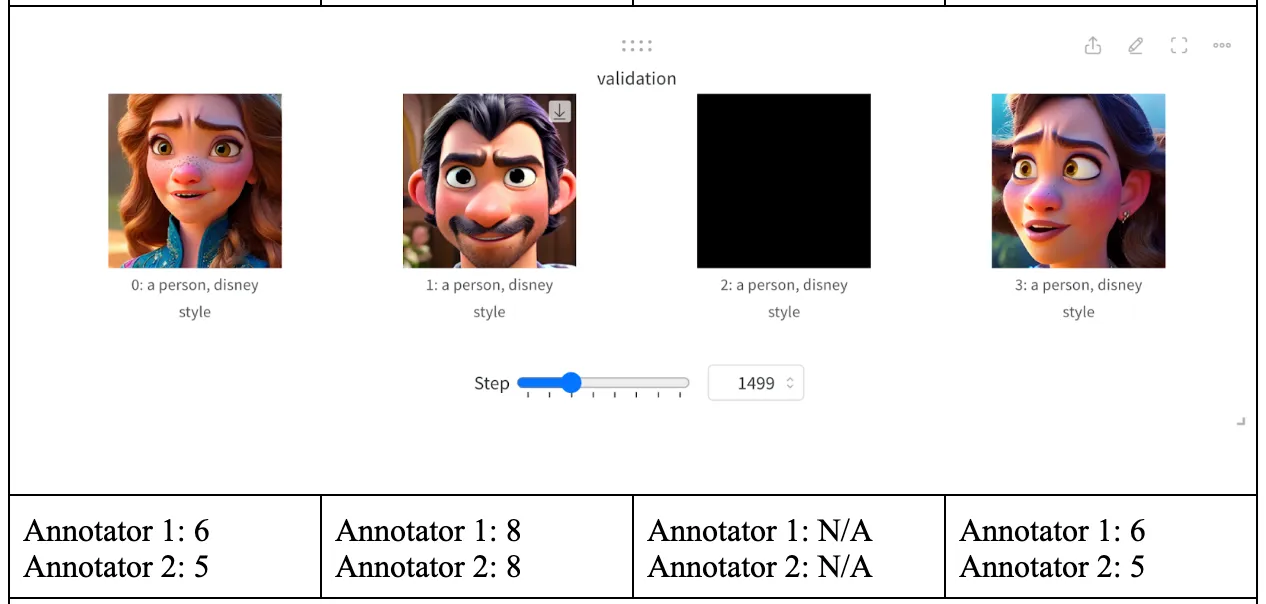

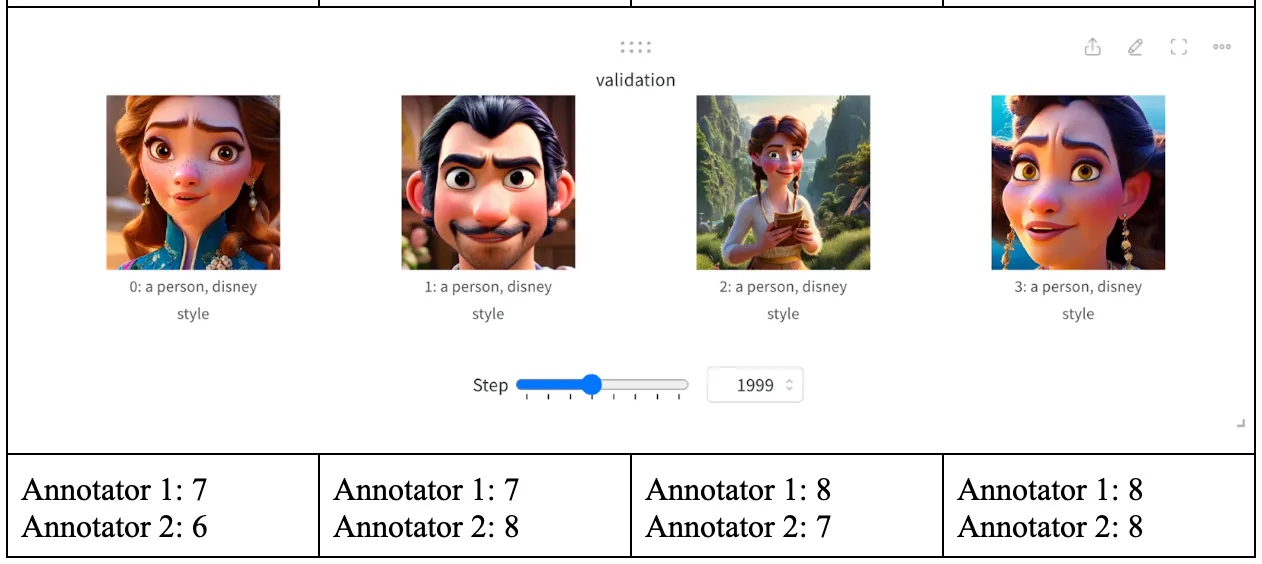

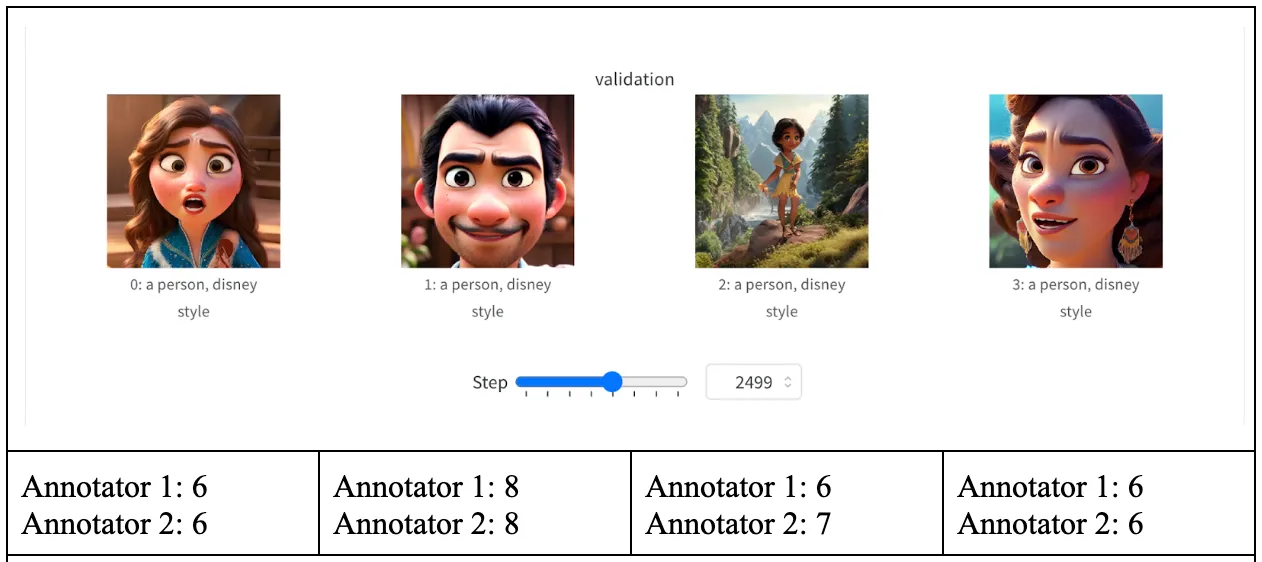

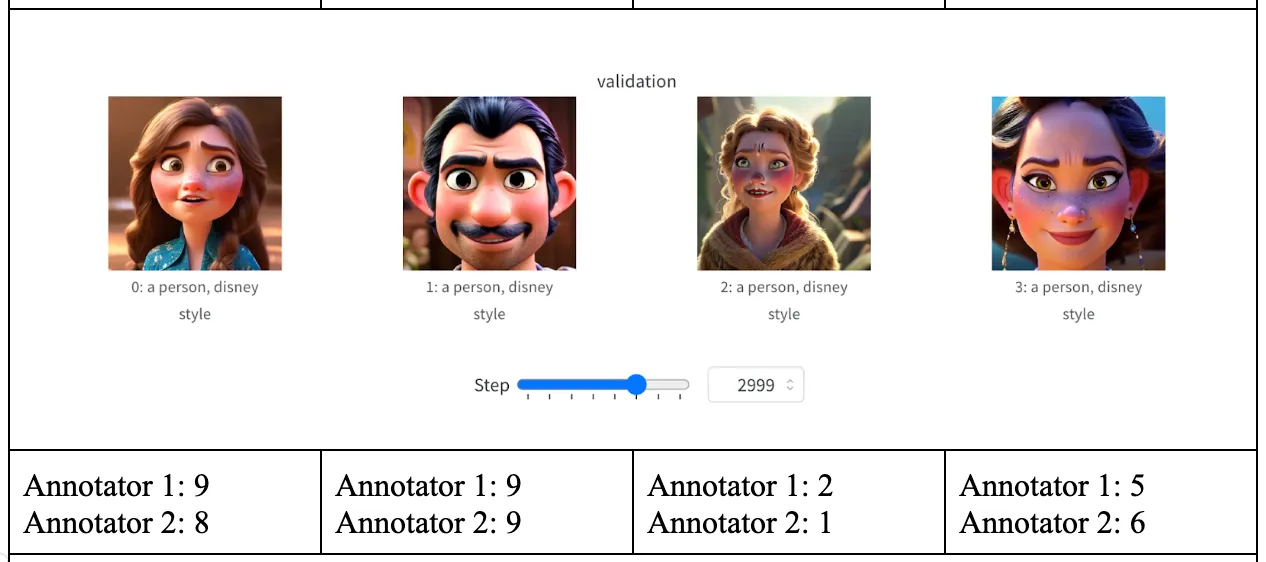

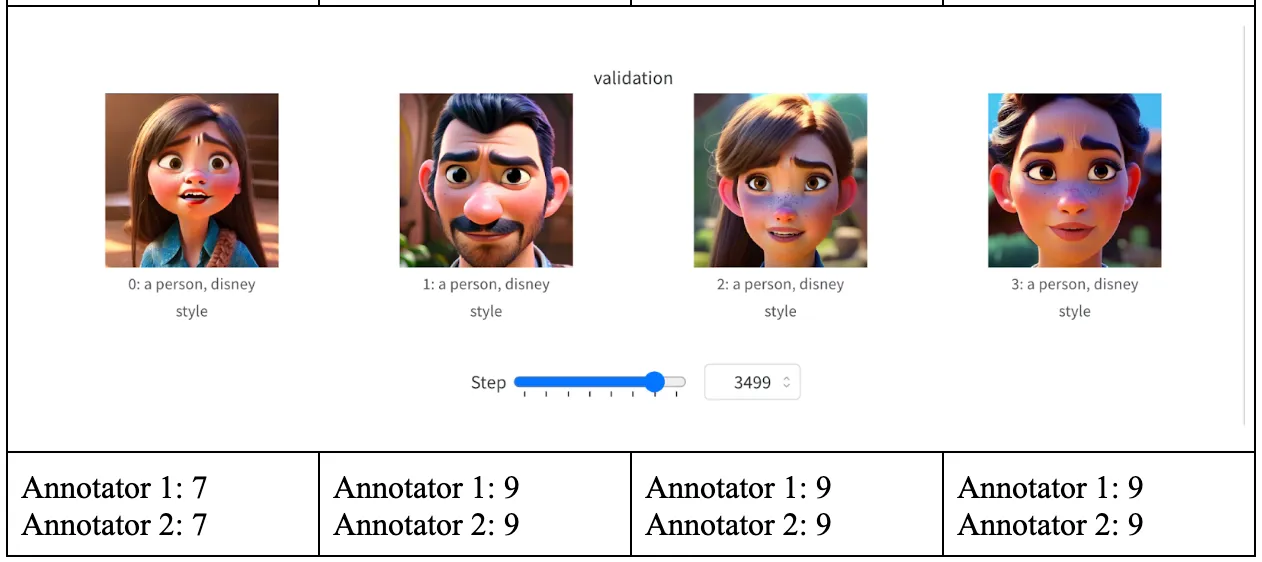

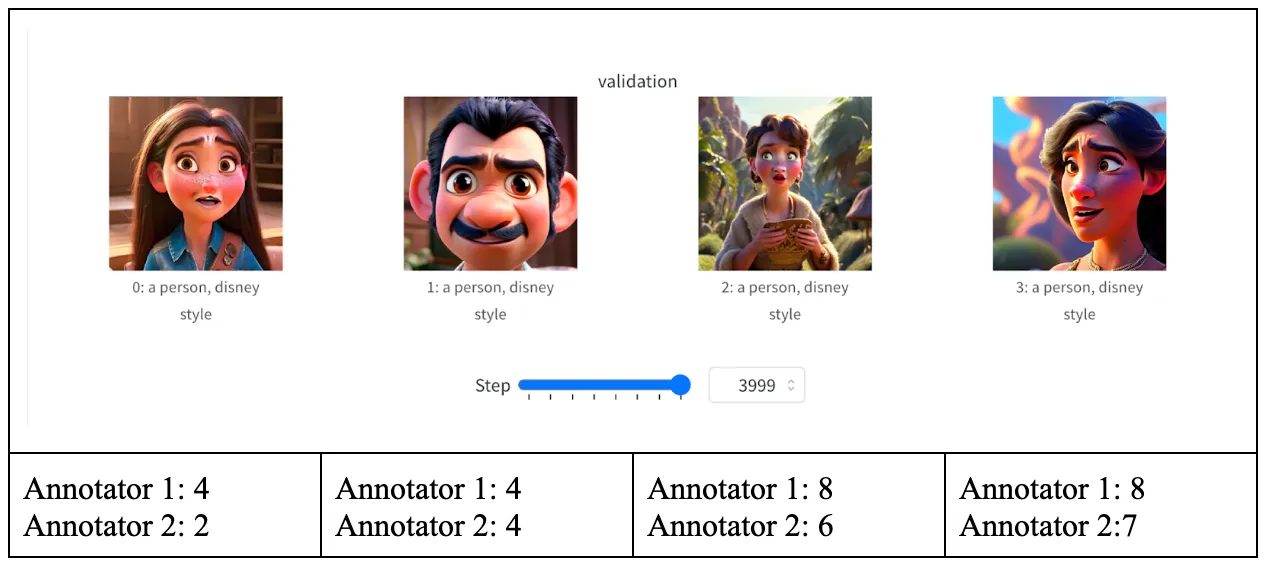

- Validation Parameters: The validation prompt was set to “a person, Disney style” to guide the model in generating images that match this theme. Four images were used for validation purposes to ensure that the style was being captured accurately.

- Training Data: The training dataset located in the ‘/data/disney’ directory was complemented with a class-specific dataset from ‘/data/style_ddim’, intended to imbue the model with a deeper understanding of the distinctive style features.

- Image Configuration: A total of 1,000 class images were provided to the model, with a prior loss weight of 1.0 to ensure that the original style attributes were preserved. The resolution was fixed at 512 pixels, and center cropping was employed to maintain focus on the central elements of the images.

- Training Procedure: To encode the text prompts effectively, the model’s text encoder was included in the training loop. The training was conducted in batches of size four over a single epoch, capped at a maximum of 4,000 steps to prevent overfitting.

- Optimizer: We implemented an 8-bit Adam optimizer to conserve memory while maintaining a learning rate of 1e-6, constant throughout the training. Beta coefficients for the Adam optimizer were set to 0.9 and 0.999, with a weight decay of 1e-2 and epsilon value of 1e-8 for numerical stability.

- Regularization and Gradient Control: The maximum norm for gradients was limited to 1.0 during backpropagation to prevent exploding gradients.

- Tracking and Precision: Model checkpoints were created every 500 steps, and training logs were recorded in the ‘logs’ directory. Mixed precision training was enforced with ‘fp16’ precision for both the model’s prior generation and validation steps to align with the selected training variant.

- Schedulers: A ‘PNDMScheduler’ was used for validation, ensuring that learning rates were adjusted appropriately at each step of the validation process.

- Reproducibility: A random seed value of 42 was used to initialize the training process, which ensures reproducibility of results across different training sessions.

Each of these parameters was chosen with careful consideration of both the computational efficiency and the specific stylistic goals of the project. The train script can be found here.

Results

Since the outputs of the model are images, valid quantitative evaluations are ambiguous. For quantitative evaluations, we decided to rate the images from each checkpoint and see if there has been improvement of image generation quality. The ratings range from 1 (poor quality) to 10 (great quality). Note, in the third set of images, an entirely black image is triggered by the Stable Diffusion image safety checker model. Therefore, we did not evaluate the particular image.

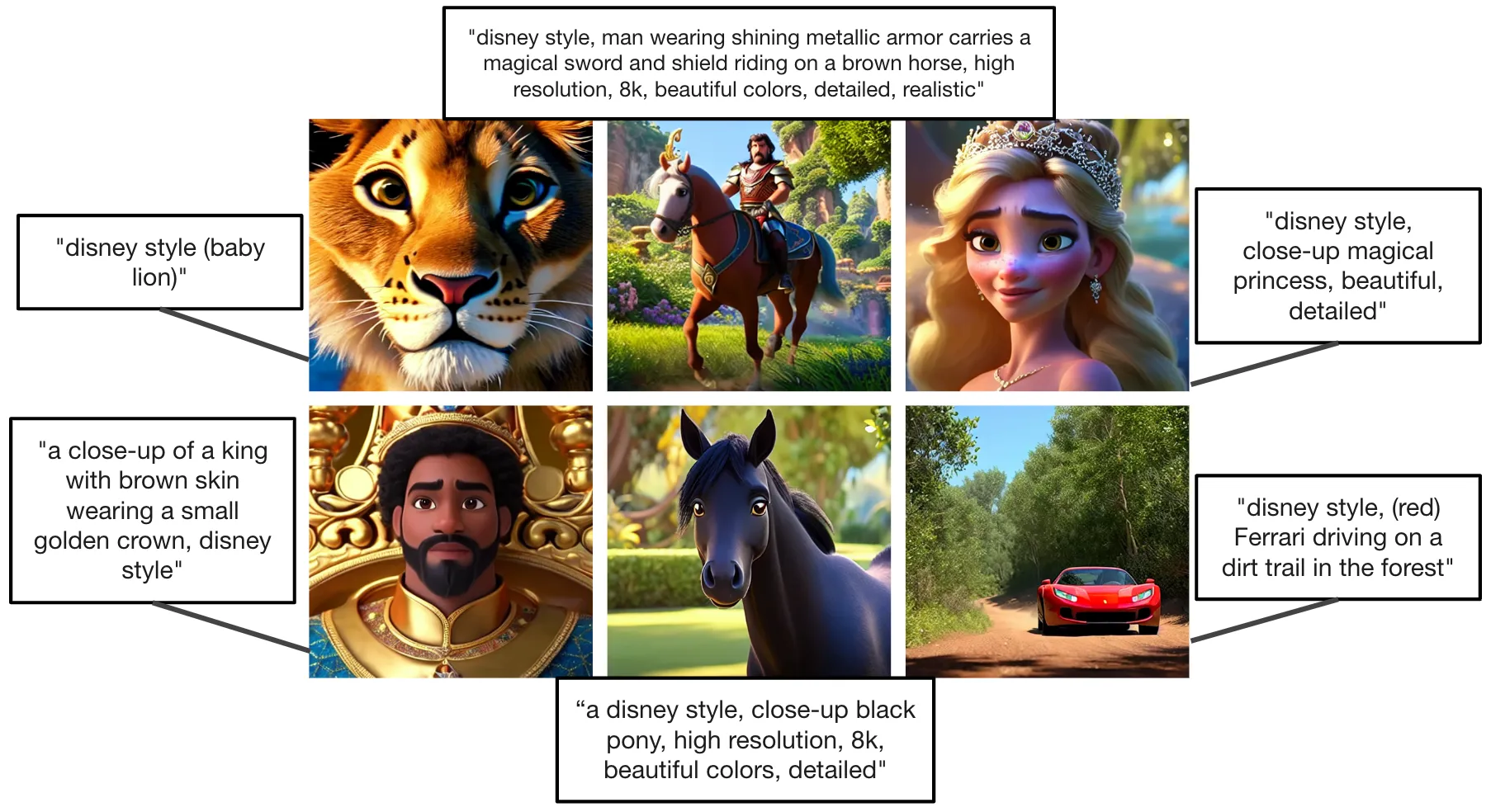

Throughout the training process, we evaluated the generated images at intervals of 500 steps to assess their quality. The average scores at these intervals were calculated to track the progression of image quality. At 500 steps, the initial images received an average rating of 3. Subsequent assessments showed improvement, with average ratings rising to 3.5, then peaking at 8.625 after 3500 steps, which marked the highest image quality during our experiments. Notably, after 3500 steps, a slight regression was observed, culminating in an average rating of 5.375 by the end of 4000 steps. We also include hand-picked images from the final checkpoint in the Supplementary Material section.

These observations suggest that while there was an improvement in the quality of the generated images throughout most of the training, a decrease in quality was noted towards the end. This trend underscores the complex relationship between training steps and image quality, indicating a possible overfitting or a need for adjustment in the training parameters beyond the 3500-step mark.

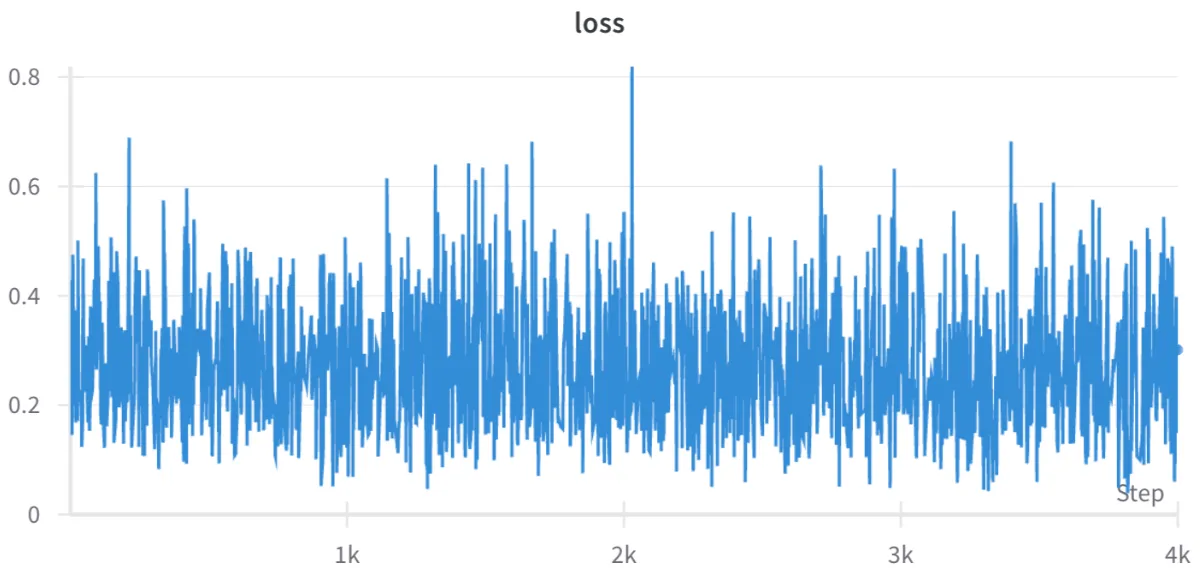

Another metric that we check is the cross entropy loss during the training process. As you can see below, the loss fluctuates quite a bit which may be expected for such a small dataset on the order of hundreds of samples.

Conclusion

The exploration of DreamBooth’s training capabilities revealed a number of critical insights, particularly relating to its sensitivity to hyperparameters and the potential for overfitting. It was discovered that a low learning rate was paramount for stable convergence, while the training duration needed to be proportional to the size of the dataset to avoid overfitting while still capturing sufficient details. The incorporation of prior preservation, especially when training on nuanced subjects like faces, proved to be crucial for maintaining the integrity of generated images. The refinement of the text encoder emerged as a significant factor that influenced the final output quality. This fine-tuning, when carried out with the adjustments to the U-Net model, led to substantial improvements in the fidelity of the generated images. Dedicated prompt engineering was another critical element, substantially impacting the relevance and specificity of the generated images. Careful crafting of prompts ensured that the model’s outputs more accurately reflected the desired themes and styles. Furthermore, experimentation with various noise schedulers like Euler A highlighted the importance of these components in the image synthesis process. In our specific case, the Euler A noise scheduler was particularly effective, enhancing the model’s ability to produce high-quality images.

In conclusion, the process of training DreamBooth requires a delicate balance between a multitude of parameters and training nuances. Our findings underscore the importance of a methodical approach to training parameter configuration, which can lead to remarkable results that push the boundaries of generative models when executed with precision.

References

- “Training Stable Diffusion with Dreambooth using 🧨 Diffusers.” https://huggingface.co/blog/dreambooth

- Mishira, Onkar. “Stable Diffusion Explained.” https://medium.com/@onkarmishra/stable-diffusion-explained-1f101284484d

- Ruiz, Nataniel et al. “DreamBooth: Fine Tuning Text-to-Image Diffusion Models for Subject-Driven Generation.” https://arxiv.org/pdf/2208.12242

Supplementary Material

👥 Collaborators

- Yewon Lee (Boston University)