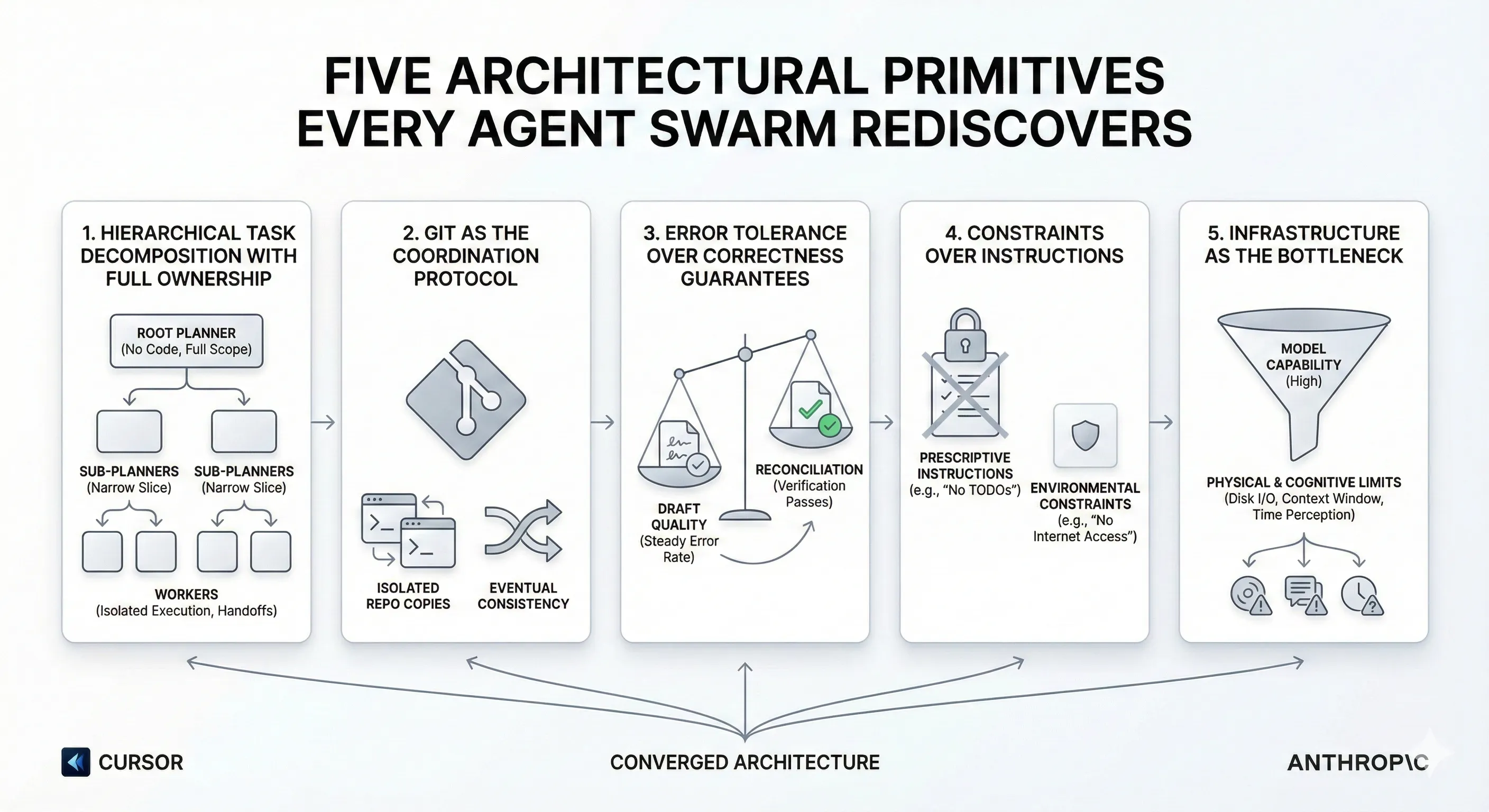

Five Architectural Primitives Every Agent Swarm Rediscovers

Two Experiments, One Architecture

Two engineering teams independently published results from ambitious multi-agent coding experiments. Cursor ran thousands of agents for a week to build a web browser from scratch, peaking at ~1,000 commits per hour across 10 million tool calls. Anthropic ran 16 Claude agents for two weeks to build a C compiler in Rust, producing 100,000 lines of code across nearly 2,000 sessions for $20,000 in API costs.

Different teams. Different models. Different goals. They converged on the same five architectural primitives.

This post breaks down each primitive with implementation details from both projects, explains why the convergence happened, and gives you concrete patterns to apply in your own agent systems.

Primitive 1: Hierarchical Task Decomposition with Full Ownership

Both teams discovered that flat agent structures fail catastrophically at scale.

Cursor’s Journey to Hierarchy

Cursor started with the intuitive approach: give all agents equal status and let them self-coordinate through a shared file system. The result was disastrous.

“Agents held locks for too long, forgot to release them, tried to lock or unlock when it was illegal to, and in general didn’t understand the significance of holding a lock.”

Twenty agents slowed to the throughput of two or three. Worse, flat structures induced responsibility avoidance. Agents chose smaller, safer changes rather than tackling core challenges.

The breakthrough was a three-tier architecture:

Root Planners own the full scope. They read the codebase, understand the architecture, and decompose into thousands of tasks. Critically, they write zero code. This keeps their context window clean. Sub-Planners recursively own narrower slices. Workers execute in complete isolation on their own repository copies, producing structured handoffs on completion.

Anthropic’s Specialization Model

Anthropic took a flatter but still hierarchical approach. Rather than recursive planners, the team let agents self-select tasks while introducing role specialization:

Agents just picked the “next most obvious” problem. Some specialized. One handled duplicate code, another focused on performance, a few critiqued design like a Rust expert would, and others updated docs.

The key insight is the same: dedicated ownership prevents responsibility diffusion. Whether you achieve it through recursive planners (Cursor) or role specialization (Anthropic), the agent that owns a problem must have full autonomy over its domain.

Both teams also discovered that a centralized integrator role backfires. Cursor explicitly removed theirs:

“We originally added an integrator for central globally-aware quality control… It quickly became an obvious bottleneck. There were hundreds of workers and one gate.”

Primitive 2: Git as the Coordination Protocol

Neither team built a custom message bus, event queue, or shared database. Both chose Git.

Cursor: Isolated Repository Copies

Each worker operates on its own full copy of the repository. There is no shared filesystem, no real-time state synchronization, and no inter-agent communication. Workers push completed changes and move on. Planners periodically pull to assess the current state.

Anthropic: Docker + Bare Upstream Repo

Each of the 16 Claude agents runs inside its own Docker container. A bare Git repo is created, and each container mounts it at /upstream. Agents clone locally to /workspace, do their work, then push back.

Task coordination uses lock files in Git:

# Agent claims a task by writing a lock filecurrent_tasks/parse_if_statement.txt # Agent Acurrent_tasks/codegen_function_definition.txt # Agent B

# If two agents try to claim the same task,# git's synchronization forces the second to pick a different oneThe agent execution loop itself is minimal:

while true; do claude --dangerously-skip-permissions \ -p "$(cat AGENT_PROMPT.md)" \ --model claude-opus-4-6 \ &> "$LOGFILE"doneWhy Git Works

Git provides eventual consistency out of the box. Both teams discovered this is the right consistency model for agent swarms. Cursor describes it directly:

“Sometimes multiple agents touch the same file… Instead of trying to stamp these out completely or overengineer a solution, we accept some moments of turbulence and let the system naturally converge.”

This mirrors how distributed systems handle concurrent writes. Accept temporary divergence and reconcile later. The alternative (strong consistency via locking) was tried and rejected by both teams because agents are unreliable lock holders.

Primitive 3: Error Tolerance Over Correctness Guarantees

Neither team requires every commit to be correct. Both converge on correctness through iteration.

Cursor: Managed Error Rates with Reconciliation

Cursor explicitly traded commit correctness for throughput:

“When we required 100% correctness before every single commit, it caused major serialization and slowdowns… Allowing some slack means agents can trust that other issues will get fixed by fellow agents soon.”

Their approach: maintain a stable error rate. Not zero, but steady and manageable. A separate agent periodically takes snapshots of the main branch and does “fixup passes” to produce a clean “green” branch.

Anthropic: GCC as an Oracle

Anthropic hit a wall when all 16 agents converged on the same Linux kernel compilation bug, overwriting each other’s fixes. The solution was to use GCC as a known-good oracle:

This turned one monolithic debugging problem into many independent, parallelizable ones. Each agent chased different bugs in different files. The compiler eventually reached a 99% pass rate on the GCC torture test suite and could compile PostgreSQL, Redis, FFmpeg, DOOM, and a bootable Linux kernel.

The Pattern

Both teams treat agent output as draft quality by default and rely on verification passes to ratchet toward correctness. This is the same principle behind optimistic concurrency control in databases. Let operations proceed without locks and reconcile conflicts after the fact.

Primitive 4: Constraints Over Instructions

Both teams found that telling agents what NOT to do outperforms telling them what TO do.

Cursor’s Negative Constraints

“Constraints are more effective than instructions. ‘No TODOs, no partial implementations’ works better than ‘remember to finish implementations.’”

Cursor also found that prescriptive task lists cause agents to enter a “checkbox mentality”. Focusing on completing listed items rather than understanding intent:

“Avoid checkbox mentality for higher-level or deeper tasks. Give detailed instructions about your intent, but remember giving specific things to do tends to make the model focus on achieving those rather than the wider scope.”

Anthropic’s Clean-Room Environment

Anthropic took constraints further by making them environmental rather than instructional. Each agent operated in a Docker container with no internet access, only the Rust standard library available. This is not a prompt instruction. It’s a physical constraint that cannot be circumvented.

The harness also constrained output volume to prevent context pollution:

“The test harness should not print thousands of useless bytes. At most, it should print a few lines of output and log all important information to a file.”

Why Constraints Win

This maps directly to the principle of least privilege from security engineering. Granting agents broad capabilities and then instructing them not to use certain ones is inherently fragile. Removing the capabilities entirely is robust. The same principle applies to prompt engineering: negative constraints (“never do X”) create harder boundaries than positive instructions (“remember to do Y”).

Primitive 5: Infrastructure as the Bottleneck

Both teams found that the model was capable enough. The surrounding infrastructure determined success or failure.

Cursor: Disk I/O and Tool Contention

Cursor ran their harness on a single large Linux VM. The bottlenecks were physical:

“After limiting RAM usage of agents, the disk became the hotspot. Especially with a monolith project, hundreds of agents compiling simultaneously would result in many GB/s reads and writes of build artifacts.”

Shared tool locks compounded the problem:

“Many tools like Git and Cargo use shared locks, largely as a simple concurrency control mechanism.”

Anthropic: Context Pollution and Time Blindness

Anthropic’s infrastructure challenges were cognitive rather than physical:

Context pollution. Verbose test output filling the context window with noise, crowding out useful information. The fix: constrain test output to a few lines and log details to files.

Time blindness. Claude cannot tell time. Left unconstrained, an agent would spend hours running exhaustive test suites without making progress. The fix: a --fast flag that runs a 1% or 10% random sample, deterministic per-agent but random across VMs so collective coverage remains complete.

“The team had to constantly remind themselves that they were writing this test harness for Claude and not for themselves, which meant rethinking many assumptions about how tests should communicate results.”

The Infrastructure Checklist

If you’re building agent systems, these are the infrastructure problems to solve before worrying about model selection:

| Category | Cursor’s Problem | Anthropic’s Problem | General Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|

| I/O | Disk saturation from parallel builds | Context window saturation from test output | Agents amplify I/O load non-linearly |

| Contention | Git/Cargo shared locks | All agents converging on same bug | Shared resources become single points of failure |

| State | Agents drifting from original intent | Agents losing track of time | Stateless processes need continuous re-orientation |

| Observability | Logged all messages + timestamps for replay | Progress printing tuned for agent consumption | Build observability for agents, not humans |

Why This Convergence Happened

These five primitives are not new. They are the same patterns behind well-run distributed engineering organizations:

| Agent Primitive | Distributed Systems Equivalent | Engineering Org Equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| Hierarchical decomposition | Microservice ownership | Team topologies with clear domain boundaries |

| Git as coordination | Eventual consistency (CRDTs, gossip protocols) | Async code review via pull requests |

| Error tolerance | Optimistic concurrency, Byzantine fault tolerance | ”Ship and iterate” culture, feature flags |

| Constraints over instructions | Principle of least privilege, sandboxing | Security policies, guardrails over guidelines |

| Infrastructure investment | Capacity planning, backpressure | Platform engineering, internal developer tools |

As Cursor observed:

“There’s a poetic resemblance in this research to how some software teams operate today. These models were not explicitly trained in this way, which suggests it’s emergent behavior and possibly the correct way of structuring software projects after all.”

The difference is that agents are stateless processes that need orientation materials every time they spin up. Cursor addresses this with scratchpad.md files that agents rewrite (not append to) frequently. Anthropic addresses it with AGENT_PROMPT.md files and mandatory README documentation that agents maintain as they work.

This mirrors the 12-factor app principle of disposability. Processes should start fast, die cleanly, and carry no irreplaceable state. The emerging “12-Factor Agents” framework makes this connection explicit: own your context window, own your control flow, and treat agent state as ephemeral.

Applying These Primitives

If you’re building or evaluating multi-agent systems, here’s what to prioritize:

Think deeply about infrastructure. Both teams spent significant effort on test harnesses, observability, and environment design. Anthropic put it directly: “Most of our effort went into designing the environment around Claude. The tests, the environment, the feedback. So that it could orient itself without us.”

Use Git for coordination. Don’t build custom orchestration. Give each agent an isolated workspace (worktree, branch, or full clone) and let Git handle synchronization. Accept merge turbulence. It resolves faster than lock contention.

Design for error tolerance. Don’t gate every commit on correctness. Instead, maintain a reconciliation loop: a separate agent or CI job that periodically produces a clean “green” branch from the noisy working state.

Constrain, don’t instruct. Remove capabilities agents shouldn’t use rather than telling them not to use them. Restrict network access, limit filesystem scope, cap output verbosity. Environmental constraints are more reliable than prompt instructions.

Decompose hierarchically with ownership. If you need more than 3-5 agents, introduce a planner layer that doesn’t write code. If planners get overwhelmed, let them spawn sub-planners. Never introduce a centralized integrator. It will become a bottleneck.

Key Takeaways

- Two independent teams (Cursor and Anthropic) converged on the same five architectural primitives for multi-agent coding systems without coordinating

- Hierarchical task decomposition with full ownership at each level outperforms flat agent structures by an order of magnitude

- Git is emerging as the de facto coordination protocol for agent swarms, favoring eventual consistency over real-time synchronization

- Telling agents what NOT to do consistently outperforms prescriptive instructions

- Infrastructure (disk I/O, context windows, time awareness) is the actual bottleneck, not model capability

References

- Cursor: Towards Self-Driving Codebases. Full technical writeup on the planner-worker-judge architecture

- Anthropic: Building a C Compiler with a Team of Parallel Claudes. Anthropic’s account of the 16-agent compiler project

- Claude’s C Compiler on GitHub. The 100,000-line compiler source code

- 12-Factor Agents. Principles for production LLM applications, inspired by the original 12-Factor App methodology

Stay in the loop

New posts delivered to your inbox. No spam, unsubscribe anytime.